This year marks 75 years of Indian Independence, however, accompanying this illustrious moment is the ever-lurking shadow of one of the most tragic and violent episodes of Indian history- Partition, an event in history which also completed 75 years in 2022. Cutting across an entire landmass and dividing its people, separating families, causing the loss of home and putting into absolute disarray the very idea of a homeland and identity, Partition, apart from its social, political and administrative chaos, also carries the burden of an irreparable human cost, an unerasable debt. The Literature of Partition documents and recalls the stories of displacement, loss, troubled human psyche, and reflects upon the violence, bloodshed and the lingering trauma that grips the people.

Notable Writers/Poets and there work.

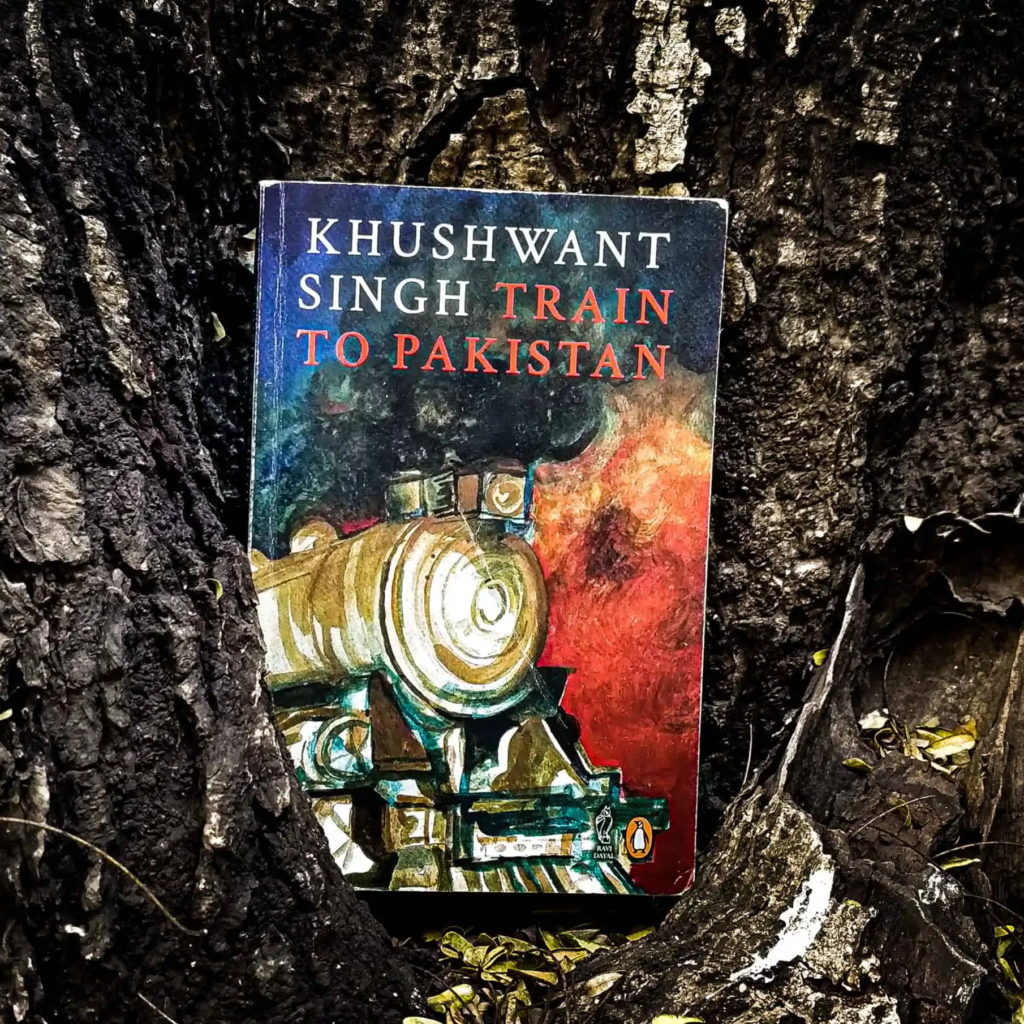

One of the most enduring features of Partition Literature is its sense of despair over the divide, the split and the sense of mutilation inflicted on the people. Khushwant Singh’s Train to Pakistan, set in a fictional border village, depicts the tragic horrors of a land divided and the violence that erupts in the wake of partition. An ordinary village with ordinary folk but as we proceed, we find the cracks of separatist tendencies developing in the community and people suddenly being instructed to leave their home for their new country. The sense of pain emanating from a brutal division and the total conundrum is felt in the narrative. As distrust and insecurity creeps in, insidious plans are made to massacre the passengers who will take the eponymous train to their new home. Jagat Singh risks his life to foil this plan and the climactic sequence that depicts his actions ensuring a safe passage to the passengers reflects in the mutilated body of the man the mutilation of motherland, of brotherhood and the division of home, of society.

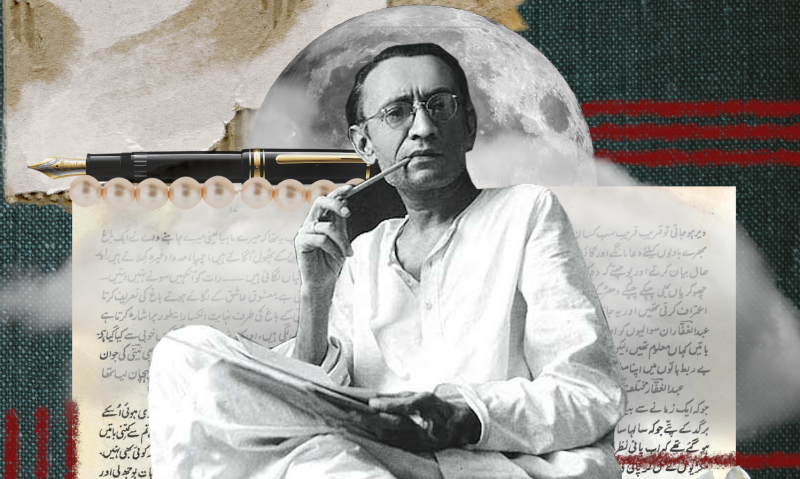

Like Khushwant Singh, Saadat Hasan Manto was also a vehement critic of Partition. Manto refused to mince his words or shy away from stating the truth. Of the Partition of 1947, he observed: “Hindustan had become free. Pakistan had become but man was still slave in become independent soon after its inception but man was still slave in both these countries–slave of prejudice…slave of religious fanaticism…slave of barbarity and inhumanity.” Manto’s stories refuse to sugarcoat the gory, inhuman acts that were committed during this time. In both his partition and other stories, Manto is known to hold up a mirror to society clearly showing the prejudices and evils that plague it. Stories like “Khold Do,” “Thanda Gosht” and others depict the horrors of Partition, calling out the brutal monstrosity of man as he turns woman into an object of territorial conquests. Manto is adept in depicting the emotional state of his characters through his narration. When the young girl in “Khol Do” is finally brought back to her already anxious father, she appears shocked into silence. At the end of the story, it is her traumatic reaction that reveals the brutal assault she had to go through. We don’t hear her voice. She is silent throughout the story. She has been forced into silence. Manto’s writing is evocative, gripping and direct. He sympathizes with the victims of Partition, he is sensitive in his portrayal of their suffering and he ensures that his protest, anger and disillusionment with the system echo in all his stories.

A post-partition tale, Manto’s “Toba Tek Singh” puts the lens on the futility of the Partition tragedy and also examines the idea of ‘madness.’ “Toba Tek Singh” takes place in a mental asylum housing patients from both countries. These patients are, however, unaware of the big political changes that have occurred outside. Bishan Singh from the village of Toba Tek Singh has been a patient in the asylum for years but now the authorities have decided to exchange these patients between the two countries like prison inmates had been exchanged “As to where Pakistan was located, the inmates knew nothing…If they were in India where on earth was Pakistan? And if they were in Pakistan, then how come that until the other day it was India?” As the story proceeds, we find out that Bishan Sigh is also called Toba Tek Singh, and this difference between the man and the place becomes less clear since he keeps asking the location of his village after partition. Is it in India or in Pakistan? The confusion remains and he is given no satisfying answer. In the end, unsure where home is, where the village lay after the Partition, the poor old man succumbs to exhaustion on the border where the exchange was supposed to take place. “There, behind barbed wire, on one side, lay India and behind more barbed wire, on the other side, lay Pakistan. In between, on a bit of earth which had no name, lay Toba Tek Singh.” Thus, the man has become synonymous with the land, in the end lying in between, or rather dying between the borders of the two states. It is not simply the tale of a mad man who is unable to come to terms with Partition, the creation of two states, rather it is the mental conundrum of not knowing where home is, the agony of losing the way home and finally losing home itself.

The illustrious poet, Faiz is also known to have recorded his dismay and the agony he felt over the wave of violence that washed over the pair of newly independent countries in “Subh-e-Azadi.” The opening lines of the verse register the dark mood and defeated tone of the speaker:

ye daaġh daaġh ujālā ye shab-gazīda sahar vo intizār thā jis kā ye vo sahar to nahīñ ye vo sahar to nahīñ jis kī aarzū le kar chale the yaar ki mil jā.egī kahīñ na kahīñ

Faiz’s “Subh-e-Azadi” is now recognized as one of the significant texts bemoaning the horrific tragedies of the partition. Writers like Qurratulain Haider and Amrita Pritam have also narrated the violence of partition, its bloody aftermath and its tragic legacy. In My Temples Too, Qurratulain Haider writes of the loss of a composite and unified culture and critiques the growing instances of communal and nationalist politics that take on separatist tendencies. Amrita Pritam’s Pinjar focuses on the experience of women during partition and offers an honest social commentary on violence and revenge, and a touching but complex portrait of womanhood. Both Qurratulain Haider and Amrita Pritam have written outstanding works of literature and have produced exceptional texts documenting the political instability, social rupture, cultural loss and the psychological disturbance that accompanied and followed the Partition of 1947.

This moment of socio-political upheaval had many writers and artists testify against its inhuman nature in their testimony of the time written in the form of stories. Bhisham Sahni also writes of the chilling incidents of the time. Tamas remains a landmark text in its depiction of partition and has also been adapted into a film. Echoing the title, the novel truly captures the darkness that fell upon the victims of partition, the darkness that divided communities, the darkness that witnessed massacre. Apart from novels, Bhisham Sahni has also authored a number of short stories.

One of his short stories, “Pali,” revolves around a young child separated from his Hindu parents amid the chaos of displacement as the “uprooted people” leave their village in a newly formed Pakistan for India. His parents’ frantic search efforts go in vain. Since their lorry must cross the border before dark, they leave, defeated and dejected. Found and raised by Muslim parents, he grows up a happy child. The child, Altaf has no memory of his birth family, having been really young when Zenab and Shakur take him in. The poetic language of Sahni’s stories pulls in the reader and better illustrates the characters’ emotions. Of the new parents, we learn that with the entry of the child, their “lives started revolving in a new orbit around Altaf. They wove their dreams around him.” However, Manohar Lal, the child’s birth father who has been searching for his son finally finds him 11 years later.

In what can be described as one of the most moving moments of the story, the child is shown two photographs to verify Manohar Lal’s claims. When he saw the first one, that of Manohar Lal and his wife, he said with a vague sense memory “Mataji!” and “Pitaji!” as a “strange restlessness seized him.” He “beamed” when he saw the second photograph, that of Shakur and Zenab and said “Abbaji! Ammi!” A heart-breaking story that confirms the universality of familial love and the pain of losing a child, the story dwells on the love and loss experienced by both sets of parents. And what of the child? We find him “lost and forlorn” as he separates from Zenab to ‘return home’ with Manohar Lal. As the story ends Altaf grows “confused” about his identity as everyone in his new home call him Pali, a shortened version of Yashpal, his birth name.

Sahni’s story about Altaf/Pali puts the lens on children’s experience, their memories and perception of events. At the same time, we are also reminded of the universal sentiments of parenthood. Zenab, Altaf’s mother feels his absence and is consumed by the loss of her son at the end of the story just as Kaushalya, Pali’s birth mother had been at the beginning of the story when she joined other uprooted people like her for her journey to India. The story does not make morally driven conclusions and the narrator ensures us that he is neither a judge of morality or justice for who can say which of the mothers have a more rightful claim on the child– the mother who gave birth to the child or the mother who raised him. Yet, the story is one of loss and longing. The narrator has shown us the reality of Partition, the ugly side of Independence.

The history of Partition is a long one and as is its literary legacy. Along with the writers mentioned here, others like Khadija Mastoor, Ahmed Faraz, Intizar Hussain, Bapsi Sidhwa, Jyotirmoee Devi and Gulzar, the popular Bollywood lyricist, have also produced literary works on the subject of Partition. With each story a different voice, a different experience is associated. Writing of the scenes they were surrounded by, the socio-politico-cultural milieu they inhabited, the writers of Partition literature documented the sufferings of the victims in their literary works. Although most of the works mentioned in this article are works of fiction, they all reflect stark realities of the time and are rooted in bitter truth. The protest of these writers is in the words they write and the stories or experiences they bring to light. They decry the bloody violence of Partition and mourn the loss of a harmonious, unified life as they knew it.